Where on earth did the effect go?

One replication is worth at least a thousand t-tests, indeed, but several replications (let’s say about twenty) and well-powered studies are worth at least a million t-tests.

A proper manner to uncover fraudulent-, flawed-, and chance findings is replication. Basically, a replication is nothing more than to copy-cat an earlier study, so exact as may be possible, only to see whether the results come close to those of the original paper. Positive replications, in general, add to the credibility of a finding. Negative replications, instead, can indicate fraudulent or flawed studies/behavior but also can reflect mundane issues such as the use of an underpowered sample. The American psychologist Henry Roediger captured the importance of replication in a short and nowadays famous sentence: one replication is worth at least a thousand t-tests.

Recently, some colleagues and I also entered the arena of replication. To be honest, this arena is not as sexy or exciting as the one in which the initial research findings are generated. So, what then was our drive? Well, we noticed inconsistencies with regard to a research finding that can be regarded as a pillar for the theory in our research niche. We decided that this inconsistency needed to be solved before going a step further. The inconsistency we talk about is on the relation between a variant, val66met, on the gene that codes for BDNF, a neuronal growth factor, and the volume of the hippocampus. Biologically, there are pretty good reasons for why such an association could exist. However, no theory here, we are talking methodology today. Besides, it is complicated and may bore you at least a little.

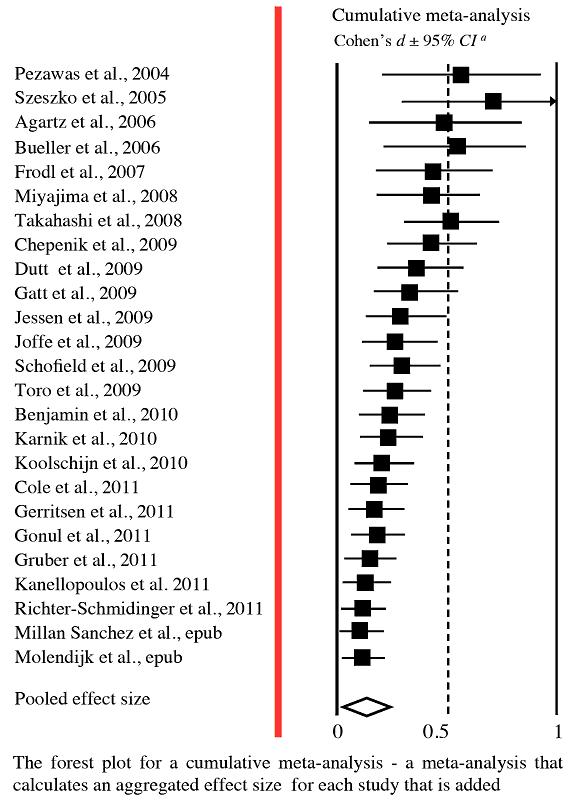

What did we do? We performed a single (replication) study and beyond that ran a meta-analysis on the subject matter. This latter, performing a meta-analysis (i.e., an analysis that estimates the strength and the direction of a presumed effect over studies) is a very useful thing to do when faced with non-uniform findings and it serves. We included a total of 25 studies (on no less then 3,620 individuals) in our analysis and found the effect we were looking for: carriers of a met allele (each individual has either 2 val alleles on this locus or one or two met alleles) had smaller hippocampal volume. This effect, however, was so small that we not really were impressed by it. What did impress us though was a striking correlation between the year in which the paper was published and the magnitude of the effect that the paper reported (see the accompanying figure for a cumulative meta-analysis that shows that the effect-sizes steadily decline over time). Our first tentative conclusion from this was that the effect of interest seems to be hard to replicate. Strengthening this tentative conclusion was that we found that small-scale studies, that are likely to be the least reliable, estimated the effect to be very large whereas the big, and probably more precise, studies estimated the effect to be non-existent. Altogether we concluded, with a broken heart and tears in our eyes, that the relation between val66met and hippocampal volume probably does not exist. Rather, the presumed association resonates a winners curse in which early studies report large effects (and get published in top-notch journals) to be followed by increasingly smaller effects in subsequent (and better powered) replication attempts (that get published in lower ranking Journals or worse, not at al: i.e., the file drawer problem).

Indeed - one replication is worth at least a thousand t-tests - but I would like to add that a couple of replications (let say about twenty) and well-powered studies may be worth at least a million t-tests.

-

Read more: 'A systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between BDNF val66met and hippocampal volume—A genuine effect or a winners curse?' (2012).