The role of honor in intercultural conflicts

As the world is changing into a place where people with different cultures live together, it is becoming increasingly important to understand cultural differences. Can social psychology inform us on how to prevent conflicts based on such differences?

Cultural clash

The relationship between the Dutch government and the Turkish community recently took a turn for the worse. Minister Lodewijk Asscher (Social Affairs) disclosed the results of a study into Turkish organizations in the Netherlands. This publication not only contributed to a heated debate within his party and the exit of two Turkish members from the parliament. It also resulted in an international quarrel with the Turkish government. However, the conclusions of the studies were indefinite at best. They indicated that the organizations in question serve to enhance both the Turkish Islamic identity (bonding) and to strengthen ties with the Dutch community (bridging). So if it was not the content of this message that caused the disagreement, what was the problem?

Honor

What Asscher seems to have overlooked is that Turkey is what social psychologists call an honor culture. In these cultures, a person’s worth is strongly tied to his/her honor. Honor reflects not only a person’s self-worth, but also his or her reputation and good name in the eyes of society. Honor cultures are found in different areas around the world, such as the Middle-East, the Mediterranean, Latin countries, and the southern part of the USA. In these cultures, maintaining a good reputation and protecting one’s social image is essential in day-to-day life. Because honor is an important aspect of a person’s identity and group membership, people will go to great lengths to protect it.

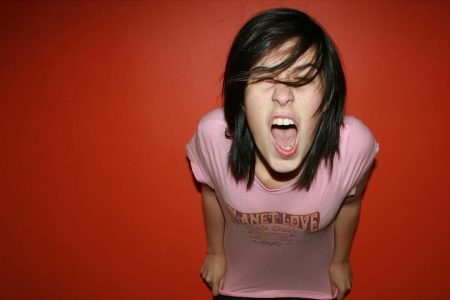

Recently, the Volkskrant published a profile on minister Asscher, describing him as “a man of confrontation”. His preferred method of operation was described as “humiliation first, discussion second”. Researchers have found that people from honor cultures are particularly reactive to being humiliated or shamed. The consequences of such provocations have been shown on emotional, behavioral as well as physiological levels. For example, when people concerned with honor are insulted, not only does their anger level rise significantly, but also their cortisol (stress) and testosterone (aggression) levels. In our own laboratory, we have found that manipulating people’s sense of honor in an experiment resulted in a heightened sense of (physiological) threat and aggression. This was even the case in participants from non-honor cultures. It seems that reliance on honor as a source of personal worth makes people sensitive to social evaluations. Not surprisingly, Asscher’s tactic of shaming seems to have backfired on him this time. Though it may have served him well before, this time is it has aroused more resistance than cooperation.

Respect

Does this mean that one should always avoid confrontation with people from honor cultures? Certainly not. However, there are many ways to go about this. The same research shows that if treated with respect, members of honor cultures often tend to be more friendly, cooperative, and accommodating than individuals from other cultures. In one study, we even found that honor-culture members were likely to share more money with a competitor after they were complimented by that same competitor than they would have if they had not been complimented. So, if your goal is to promote cooperation rather conflict with someone from an honor culture, your best bet might be to address an issue respectfully rather than offending them publicly.