Language: the Hardest Problem of Science - Easy Peasy for any Child

One of the most difficult problems of science is where language comes from. Language ontogeny – how children can learn it? – and phylogeny – how did it emerge in evolution? – are still largely unsolved mysteries today. In a recent study, we attacked the issue in the lab, with surprising results.

Also published in Dutch: Het Talige Brein

The origins of language in mankind and a child.

Where does language come from? This is probably one of the most difficult problems of science. And it comes with many collateral mysteries: How does the emergence of language relate to the emergence of consciousness; and did language come first or second? What exactly was language meant for? How did language benefit the evolution of mankind? The standard straightforward answer to that last question is ‘for communication’. Surprisingly Chomsky, still a –or the - world leading scientist on language, believes that language is not for communication, but for ‘complex thinking’. Complexity, he further argues, is embodied in grammars: extremely sophisticated pieces of software that no robot is capable of running. Yet, every child in the world learns it. Indeed, children make no mistake in understanding the multileveled recursively structured sentence Who do you think gave Auntie Jane that doggy? Computers do.

The problem has grown out of scientific control, since thinkers have separated grammar (syntax) from meaning (semantics). A sentence can be grammatical yet meaningless (the red sky is flickering under the blue tomatoes) or making sense and grammatically incorrect (the tomato red is under flickering sky blue). So, for language to emerge in a developing child and in evolution meaning must be learned separately from word order. That is, dependencies between word categories (like ‘adjectives ’ and ‘nouns’ must be learned; not the dependencies between specific words like ‘red’ and tomato’.

Computers can’t learn it

But how could a child derive this from her experiences with language when her mother gives positive feedback to incorrect sentences (“Tomato the red, Mommy ..” “Sure, yes, the tomato is red, Cathy”) and negative responses to correct sentences (“This tomato is blue, Mommy!” “No, no, that tomato is red, Cathy”).

How can language rules be learned if we cannot rely on how language appears to us: as a vehicle of meaning? One theory assumes a bootstrapping mechanism; an idea that nicely expresses the impossibility of language learning: pulling oneself up by one's bootstraps. Another seminal answer is: Indeed, we don’t learn grammar. Instead, we `acquire’ it thanks to a uniquely human predisposition, a ‘language readiness’. In other words, language is already in our brain at birth. A somewhat unsatisfying solution to many down-to-earth cognitive scientists.

Bringing the issue to the lab

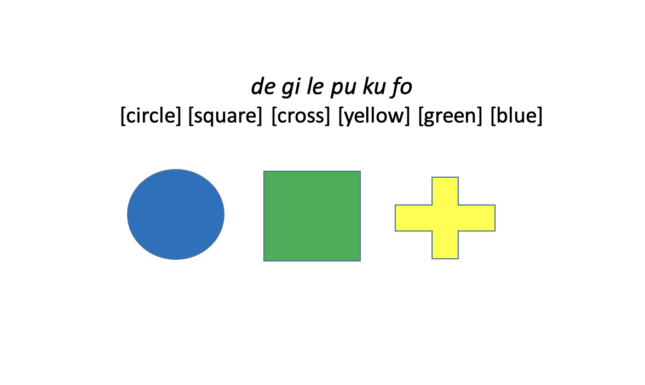

In our lab, we study the issue by simulating language learning in computer tasks. In the time course of one lab session, sitting behind a computer screen, participants learn an artificial language (made of sentences of nonsense words) that mimics natural grammar. We might expect that learning a grammar without being bothered by meaning, helps. But people turn out very bad at learning the rules of even very simple meaningless languages, as multiple studies, including ours, have shown. In a recent series of experiments, we (a team of Dutch and English colleagues) added ‘meaning’ to the mock grammar. Our miniature language had a tiny vocabulary (like pu, ko, gi etc….), with some words for colors and some that meant shapes. When a color word was correctly paired to a shape word, in a parse, they described objects in the visual world (e.g. green circle). The grammatical rules would determine what objects a sentence talked about, by positioning color and shape words in ‘grammatical’ positions. Now, our participants could ‘see’ what words were to bind together to ‘make ’the object. They could ‘see’ the grammar.

Do not try hard; do not try at all.

After having been shown a number of these sentences and their corresponding pictures, participants were given new sentences. They had to tell what these new sentences ‘mean’. Now, participants had no difficulty: they easily used the grammar to understand the meaning of new sentences they had never seen before. Moreover, participants seemed to extract grammar knowledge effortless, not by trying hard, but rather by neglecting grammar at all. Grammar knowledge manifested itself through its use for understanding, but did not enter awareness. It just was there, ready to be used for making sense of any new sentence encountered. Not to be known.

Our studies clarify one piece of the mysterious puzzle of language learning. Something like: Just forget about grammar, and look in the world for meaning. You will get the grammar for free….

Blog written by Fenna Poletiek as a result of Poletiek, F. H., Monaghan, P., van de Velde, M., & Bocanegra, B. (2021). The Semantics-Syntax Interface: Learning Grammatical Categories and Hierarchical Syntactic Structure through Semantics. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 47 (7) 1141-1155