Happiness and hormones: spring breaks, autumn falls

Our mood can be affected by the changing of the seasons. What do we understand about seasonal affective disorder (a.k.a. winter depression)?

'There is wind where the rose was, cold rain where sweet grass was, sad wind where your voice was, tears, tears where my heart was'

- ‘Autumn’ by Walter de la Mare (1906)

‘Tears, tears where my heart was’ – Clearly, the summer-autumn transition doesn’t leave Walter de la Mare as he was. Herein he does not stand-alone. The mood of many is at least somewhat affected by this inevitable yearly transition and the shortening of the length of day that accompanies it. These changes in mood often are subtle, for example in the form of a somewhat greater need for sleep and being less cheerful about having sex (i.e. having a bit of winter blues). For certain persons (2 to 8 percent of the population), however, this transition is a grim signal that heralds the commencement of a clinical syndrome: seasonal affective disorder (a.k.a. winter depression) with overeating, oversleeping, withdrawal from family and friends, and hopelessness as main symptoms. Typically, these symptoms disappear when the length of day increases in early spring; as if they were they snow for the sun.

Since about a year or ten, the scientific community got excited about the idea that affective disorders (i.e. depression) may (partly) be secondary to a low expression of Brian-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). BDNF is a hormone that boosts the plasticity and functioning of neuronal tissues that play part in emotional behavior and learning. Indeed, many studies show that the expression of BDNF is low in the depressed state and that this normalizes in the course of symptom remission. Given these links and earlier findings that show seasonality in processes and behaviors such as brain plasticity and memory that are regulated by BDNF, we set out to investigate seasonal entrainment of serum BDNF concentrations.

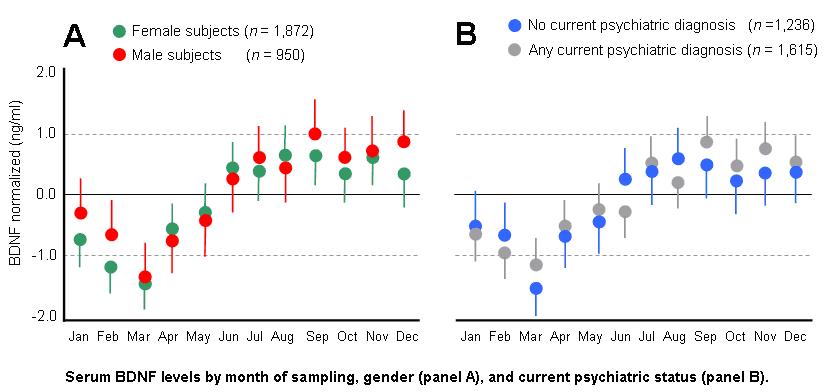

Our analyses, using data that came from a prospective cohort study (the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety), confirmed our ideas as we could pinpoint a coherent seasonal pattern of increasing BDNF concentrations over the spring/summer period (20 March tot 23 September, equinox vernal, spring breaks) and decreasing BDNF concentrations over the autumn/winter period (23 September tot 20 March, equinox autumnal, autumn falls; see the accompanying figure). In addition, and this may come as no surprise now, we found that the number of ambient sunshine hours (a major trigger to entrain seasonality) was positively correlated with serum BDNF concentrations.

Where lies the importance of these findings? For one thing, they add to the understanding of those factors that regulate BDNF expression and, importantly, we establish a link between external events (e.g. the amount of ambient sunlight) and internal events (i.e. BDNF expression) that are known to be robustly associated with behavior. Yet, of course, we did not square the circle with regard to how seasonal affective disorder comes about nor how to deal with it when it is there. Happiness is more than a hormone.

The paper on this subject can be downloaded at the website of PLoS ONE: 'Serum BDNF Concentrations Show Strong Seasonal Variation and Correlations with the Amount of Ambient Sunlight'.