Framing Autism; the Power of Language

The DSM-5 (Diagnostical and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders) is one of the most widely used diagnostic tools to classify and diagnose people for mental disorders. This manual is not a static document, but is constantly adapted in every new edition, depending on new insights, or new movements in society. Thus, sometimes diagnoses disappear, like ‘Homosexuality’ in 1973, or new diagnoses are added, like Developmental Language Disorder in 2013. In World Autism Acceptance Month April, let’s consider the official DSM-5 classification for autism, which is ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder’.

The question is, should we indeed use the label ‘disorder’? The autism community and others surrounding and supporting this community claim autism as a form of neurodiversity, not necessarily good or bad. Autistic people are different from ‘neurotypicals’: they have their own challenges, but also their own strengths. If we leave out the ‘disorder’ part, we are left with the word ‘autism’ remains, which consists of two parts: aut = self, and ism = state of being. ‘Autism’ thus means ‘a state of being oneself’ (Levine, 2017). Not a bad connotation at all, and perhaps a state we would actually wish for many autistic people.

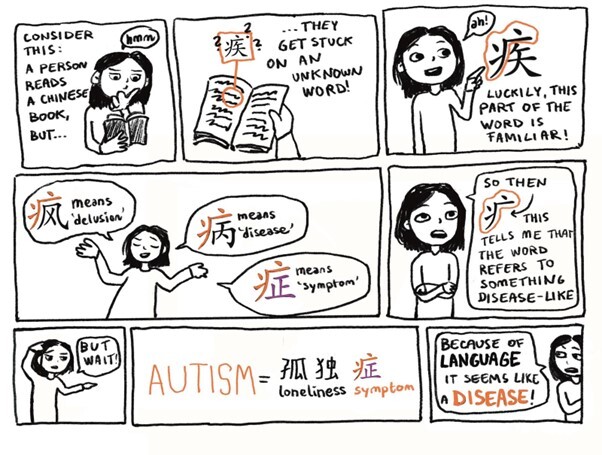

When we look at autism and the Chinese language, some other issues appear. The written language in Chinese works differently than the Roman alphabet. In Chinese, characters are made up of different parts, which represent and indicate certain categories. A Chinese character always contains one “radical”, and these radicals have several functions. Not only do they contribute to the structure of that character, but they also convey the meaning of what this character refers to. So if several characters share the same radical, this suggests that they belong to the same category. For example, in Chinese, ‘疾 (jí)’ refers to ‘injury’; ‘病 (bìng)’ refers to ‘disease’; ‘疯(fēng)’ refers to ‘delusion’. Looking into these characters closely, one can see that these characters all share the radical ‘疒’, which thus refers to something ‘disease-like’. In other words, any character that contains this radical is most likely related to physical or mental illness.

If we now check autism in the Chinese version of the DSM-5, the handbook for psychiatry, the characters used refer to ‘the loneliness symptom ( 孤独症gū dú zhèng)’ or ‘the self-shut / closing-off symptom (自闭症zì bì zhèng)’. Since 2017, the official term used by the Chinese government is ‘the loneliness symptom’, and this is also the most commonly used term in the media to denote autism. The character ‘症 (zhėng)’, which also contains the radical ‘疒’, refers to ‘symptom’. So when Chinese people read this, they will naturally relate autism to a kind of illness. Chinese scholars are trying to figure out a better way to refer to autistic people in a non-stigmatizing and respectful way. Some have suggested using ‘loneliness spectrum’ or ‘loneliness spectrum condition’, thus removing the word ‘symptom’ (Lao et al., 2024).

Apart from the characters, the way ‘autism’ is translated in Chinese contains some more negative connotations that stigmatize autism. Autistic people do not shut themselves off from society. Rather, autistic people are also part of this society, and together, autistics and non-autistics, we make up this world. Moreover, and despite common misbeliefs in the media (including Western media), autistic people also have a desire to spend time and connect with other people, instead of being alone. A great deal of research shows higher rates of loneliness in autistic people, indicating a mismatch between the desired levels of social contact and the actual levels. In interviews conducted in China by the first author of this blog, too, the interviewees expressed their strong desire to feel socially connected to family members or their peers in school.

As will be clear from the above discussion, the official word for autism in Chinese was a no-go during these interviews. Instead, the term ‘Asperger Syndrome’ was suggested by interviewees and often used; this term is transliterated in Chinese (ā sī bó gé zōng hé zhēng 阿斯伯格综合征). The radical in the character that represents ‘syndrome’ does not have negative connotations. However, Asperger Syndrome was part of the DSM-IV, but disappeared with the introduction of the newer version, the DSM-5, in 2013. In other words, Asperger Syndrome is no longer an official diagnosis, and many Chinese hospitals, which are still using DSM-IV, are currently in the process of changing to the updated version.

All in all, we are not there yet, but awareness is growing. Language matters when talking about any topic that denotes individual differences between people. These differences can easily be framed or interpreted as some people having less value, being less important, or being ‘helpless’, and this automatically invests the other with the opposite: importance, value, and power.