Depression and the potential of targeting the immune system for personalised health care

A person goes to the doctor feeling down and sleeping poorly. The doctor diagnoses depression and prescribes antidepressants. A few months later, the person is no longer depressed. Six out of 10 patients can recommend this approach, but what about the rest?

Treatments for depression work for roughly 60% of depressed patients. That’s great, but what about the other 40%? Prescribe higher dosages of medication? Different medication? Add psychotherapy? A support group? ECT? Many patients go through a trial-and-error process, trying to find what works for them, as it is hard to predict what works for whom. In other words, personalised care is lacking.

Understanding depression better

If we want to improve treatment outcomes for depression, we need to understand the condition better. The problem with depression is that there is enormous variation in the ways symptoms present, but possibly also in the underlying pathways. No two patients are the same. Can we guarantee that what works for patient A would also work for patient B? Wouldn’t it be great if – before starting treatment – we could have a better idea of what would work for this particular patient? In order to do so, we need to better understand what causes the various depressive symptoms in which patients.

One promising avenue is to look at the biology of depressed patients. Interestingly, around 30% of these patients have elevated inflammatory markers. Inflammation is an important mechanism in general immune functioning, and it is thought to be a mechanism that contributes to the onset of certain depressive symptoms.

Immunometabolic depression (IMD)

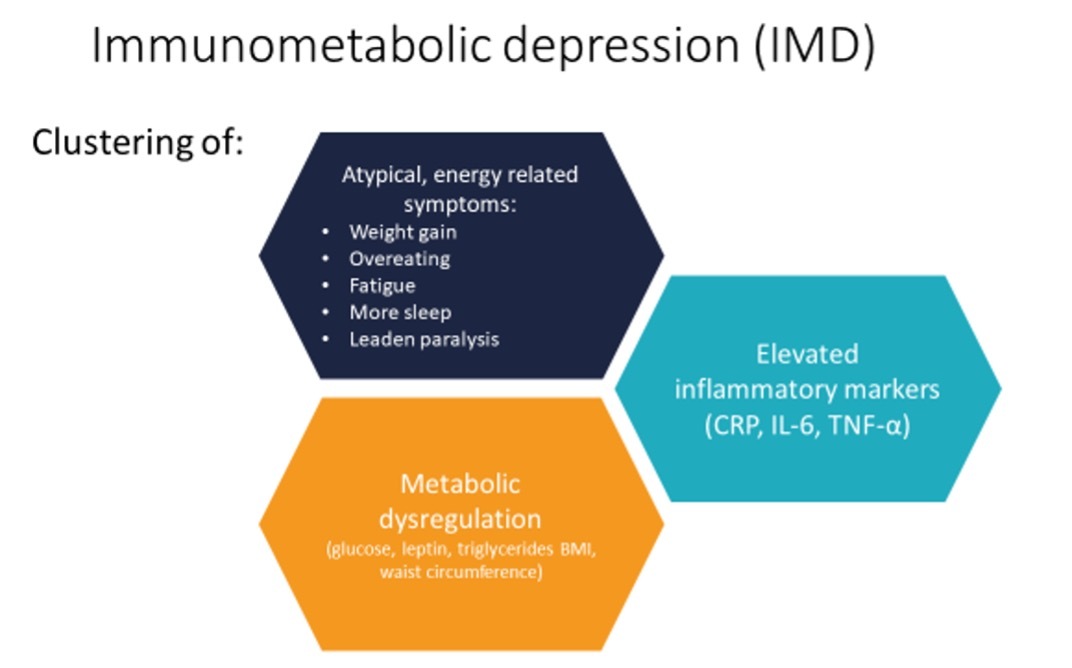

Researchers at the Amsterdam UMC have been studying this group of patients. They have found that besides elevated inflammation, these people also tend to have dysregulation in metabolic markers, with relatively higher glucose, triglycerides, cholesterol, hip circumference and BMI than other depressed patients. Interestingly, these differences are also associated with atypical, energy-related symptoms of depression: weight increase, overeating, fatigue, more sleep, and leaden paralysis. This clustering of inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and atypical energy-related symptoms has been named ‘Immunometabolic depression’ (IMD) and is estimated to be present in 30% of depressed patients.

So can simply focusing on, and treating inflammation lead to better treatment outcomes for IMD? Well, we’re not there yet.

The INFLAMED study

It is however indeed what we’re trying to find out in the INFLAMED study. In this clinical trial, 140 IMD patients will be randomly assigned to augmentation of their normal regime of antidepressants with a placebo or celecoxib (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug: NSAID) for a period of 12 weeks. The hypothesis is that in these patients, the reduction of inflammation will lead to a decrease in depressive symptoms. The study is currently ongoing; anyone who wishes to participate can sign up on the study’s website.

What will it mean if this treatment strategy is successful? Firstly, it will mean that if IMD patients are recognised, they can be treated more effectively. Secondly, it will mean a great step forward in realising personalised psychiatry. If we know that, on the basis of biomarkers and symptoms, the best way to treat psychiatric patient A subtype B is strategy 1, we no longer have to rely on trial and error. This saves time, money, and effort for everyone, and will improve the lives of patients.

It should be clear that this is the future. If effective, results could be relevant for other disorders in which elevated inflammation has been observed, such as anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. If we better understand the biology behind these disorders and start exploring treatment options for specific subgroups of patients based on biological mechanisms, personalised psychiatry has enormous potential to alter and improve the health of individuals as well as the healthcare system.