Are teenagers really missing part of their brain?

Sabine Peters has investigated how the development of cognitive and affective brain regions relates to learning and risk-taking behavior. Brain regions for cognitive control can be recruited by children and adolescents.

Find out more about Sabine Peters’ findings in this video clip.

Risk-taking during adolescence

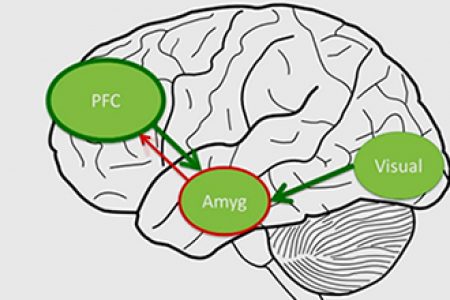

Adolescence is a period of increased risk-taking and impulsivity. This is demonstrated by teenage alcohol and drug use, for instance, and higher accident rates among this age group. Researchers have attempted to explain the higher levels of risk-taking by focusing on the development of the adolescent brain. It is thought that brain regions for cognitive control develop relatively slowly compared to ‘affective’ brain regions. Brain regions for cognitive control are involved during processes such as self-control, planning, and reasoning about the consequences of actions. Affective brain regions, such as the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens, are older in evolutionary terms; they are involved in the processing of emotions and rewards. An imbalance between the maturity of these brain regions is thought to underlie the increased incidence of risk-taking during adolescence.

Both cognitive and affective aspects of brain development

However, research findings on functional brain development remain contradictory, and few researchers have investigated the assumptions of imbalance models in large-scale longitudinal studies. Sabine Peters investigated both cognitive and affective aspects of development, using a combination of functional and structural MRI data, hormonal measures and behavioral assessments. Her study covered the whole range of adolescence in a large sample of children, adolescents and adults between 8 and 27 years old. The results indicate that, contrary to predictions from imbalance models, brain regions for cognitive control can be recruited even by young children and adolescents, but in different situations than adults. The results have implications for the construction of new theoretical frameworks and may eventually contribute to educational interventions that are better tailored to both the challenges and possibilities of the adolescent brain.