An unboxable truth

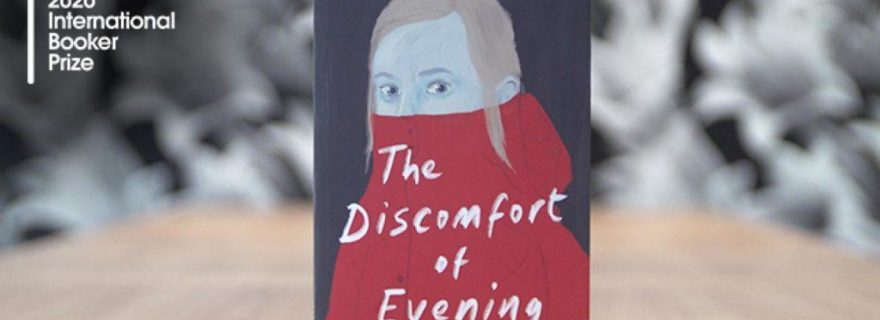

This year, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld won the International Booker Prize for 'The Discomfort of Evening'. As part of my Clinical Psychology course, I tried to paint a psychological portrait of the protagonist Jas, and to determine a diagnosis.

Determining a diagnosis for Jas turned out to be more difficult than I had thought… because in general, can you truly diagnose someone you hardly know? Can you tell, from the story they have told you, the snippets of thoughts they have shared with you, what mental disorder they have? As a clinical psychology student, I would like to say ‘yes’. Because if not, how else can I carry out my future job as a therapist? What would we, future psychologists, base our professional opinions on if not stories?

And what if your future client were a fictional character? What if she was a child, only introduced to you through printed words on paper? Would it still be possible to diagnose her? To fit her into a category that would point her towards the right kind of treatment?

Well, I’ve tried.

Rijneveld’s novel starts off with a tragedy. Jas’ younger brother falls through the ice when ice-skating, and drowns. Jas and her siblings, unnoticed by their grieving parents, each find their own way of dealing with their brother’s death. Jas decides she no longer wants to take off her jacket (the Dutch word for “jacket” is “jas”), and is suddenly incapable of going to the bathroom. She becomes anxious and develops all kinds of neurotic traits, which seem to act as ways to control her environment. She is scared of losing her parents, scared of the pain, scared of God, and scared of not being a good daughter. Eventually, to reunite with her brother and to put an end to all the discomfort, she takes her own life.

Apart from being horrified by the repercussions of Jas’s grief, I asked myself: what is wrong with Jas? I think it goes without saying that grief can be a devastating, horrible experience – but does our protagonist have to put a thumbtack into her belly button?! And what about those moments when she and her brother insert a soda can into their baby sister’s vagina? You’d have to be very open-minded not to stumble over those passages.

So I started. I tried to find out what was going on with Jas.

I began exploring trauma-related diagnoses, and wondered if Jas might be suffering from PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder). It does appear as though her brother’s death becomes a heavy burden on her. However, she does not experience any typical intrusive symptoms (i.e. nightmares, flashbacks) that come with PTSD.

What about illness anxiety disorder then (formerly known as hypochondriasis)? Jas’s main motivation for keeping her coat on is to make sure she does not get sick. She also does not want to go to the bathroom anymore, because she is afraid that small farm animals might crawl up her bum. But is this typical extreme care-seeking, or care-avoidant behaviour, as one might observe in illness anxiety patients?

Another disorder I explored was somatic symptom disorder (SSD) – where a person suffers from physical pain or discomfort without a direct physical cause. Is that what happens when Jas experiences severe stomach aches? Not really… because the physical cause seems obvious. What about depression then? The book ends in a suicide, but not all people who commit suicide suffer from depression. Also, Jas is a ten-year-old child. Can we even diagnose a minor with depression?

All in all, the DSM gives us descriptions of disorders that do not seem to fully explain Jas’s complaints. As a friend of mine who’s struggling to find the right treatment for her complaints described it recently: “if symptoms are too mild, and at the same time too unorthodox, you don’t fit into a DSM box”.

So the question is whether diagnosing Jas is actually in her best interest. Wouldn’t it be better if, instead of us trying to determine what’s wrong with her, we focused on what she is trying to tell us? If we do that, we might end up with something more useful.

Jas’s story may be an embodiment of the feeling that we cannot be prepared for when a loved one passes away. It can be a sneak peek into the mind of a young girl who is suffering, as well as trying to survive. For the clinical field, Jas’s story can be a beautiful source of atypical psychological complaints. It can be the story of a single person, or the stories of thousands of undiagnosable others.

It can be an unboxable truth.